For too many people, Foursquare is the irritating app which slightly-too-geeky friends use to spam their location on Facebook and Twitter.

The company has become synonymous with the concept of "checking in" to a place, marking your location on the internet for all to see. Even after the idea was shamelessly nicked by Facebook and incorporated into its newsfeed, it's Foursquare which remains the best-known implementation.

But the world has changed since it launched in 2009, and the idea of letting all your friends know where you are doesn't have quite the same cachet in 2014. Which is a problem for Foursquare, because even though the public's image of the company has stayed the same, what it makes has come a long way.

The flagship product is no longer the check-in function, but an app which uses that half-decade of data to present information about what's going on around you.

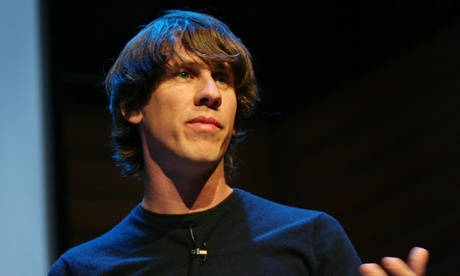

"I think the search tools and technology we've built are some of the best that have ever been built for local search," says Foursquare's CEO, Dennis Crowley, when we meet in the company's office just up Broadway from the Guardian's New York HQ.

"I think we're better than Google in a lot of cases," Crowley continues. "I think we're better than Yelp almost always."

From my own experience using the company's app, that boast may not be far from the truth. Foursquare's collection of data, built over five years of users reporting their position back to the company, now covers 60m locations from museums to mausoleums.

It uses an individual's history to build a profile of the sort of places they are likely to enjoy visiting, and employs location-awareness to offer suggestions even when the app isn't open. Those can be disabled, but are smartly-applied enough that you won't want to.

So if the product is so good, why is the company struggling?

Telling the right story

The early Foursquare was a victim of its own success. The app was a spiritual successor to Dodgeball, a service Crowley and fellow NYU student Alex Rainert developed in 2003. Before it was acquired by Google in 2005, and eventually succeeded by Google Latitude, Dodgeball allowed users to use text messages to share their location with each other. At its best, it allowed for a sort of proprioception of friendship: users always knew where they could go to find the people who they knew and liked, and were free to hang out.

Foursquare launched in 2009 with a similar idea. Users would check-in to a location, and then the app would share that info with friends. A layer of gamification on top ensured that users would be even more likely to share their location, awarding points for checking in, and giving the title of "mayor" to the person who had checked in most in a single location.

"I think our intent back then was, "hey, these game mechanics will be interesting for 4-6 weeks for people, and then we'll retire them". And it turns out they were interesting for, like, 4-6 years instead of months or weeks," Crowley says.

But while the app continued to evolve, public perception didn't. "As the company has moved from being about check-ins, to being about local recommendations based off of all those check-ins, to being about proactive recommendations based on our understanding of the world," he says, "I think our version of the story is disconnected from the public version."

Swarm

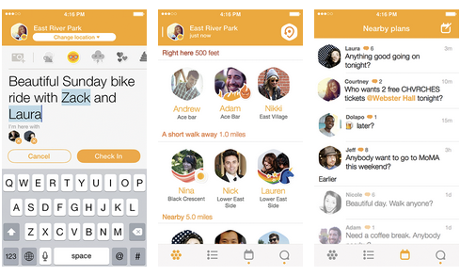

In an effort to fix that disjunction, Foursquare is making its boldest move yet: splitting the product in half. The location-aware city guide will continue to be the main app, and will receive a major update in the summer. But the checking-in mechanic, and all the corresponding social activity, is being hived off to a whole new app, called Swarm.

"The simple story with Swarm is that this is an app that has just four basic screens in it, and it's the fastest and easiest way to keep up and meet up with your friends," Crowley says. The app benefits from technology enhancements that were impossible in the early days of Foursquare, making checking-in a breeze (Swarm "is probably what foursquare would have been if it was invented in 2014 instead of 2009," Crowley adds), but just as importantly, it removes that mechanic from the main Foursquare app.

"We found that it's very difficult to tell two stories at the same time, with the same weight, in one app," Crowley says.

Split focus

While Foursquare's decision to split the firm's flagship product may be one the most drastic, it's by no means the first tech firm to come out with a slimmed-down, focused version of its core competency.

Facebook's Paper app is one example, aiming to restore readability to the company's cluttered news feed. Dropbox's Carousel is another, taking the image-handling capabilities of the main app and expanding and refining them for a stand-alone product. Neither of those companies have – yet – followedFoursquare in removing the functionality from their main product, but it may only be a matter of time.

"I think what we're starting to see is that the best apps tend to be the simplest, the easiest to use and the fastest to use," says Crowley. "Sometimes you have an app that has a lot of stuff baked in to it, and it confuses the story a bit.

"It's easy to keep adding things to an app. The real hard part is editing. I think there's a lot of other companies that are struggling with similar challenges. How do you tell multiple stories from a complicated app to a consumer that's used to really simple apps?"

But even while it fights to get customers to focus in the right place, Foursquare is financially on the right track. It's making "significant revenue" through six different products – four are varies forms of adverts shown through the service, while the other two, data licensing and merchant services, use it's technical backbone.

"There are a lot of people who are like, 'how is this thing ever going to work?' And I tell them it's been working for two years. We're doing pretty well over here."

Its cache of data alone is enough to stop Foursquare being written off entirely. Even if its public profile were to carry on shrinking, developers of apps such as Moves, Citymapper, and – until Facebook forced it to move in-house – Instagram know it as the best source of location data available.

But to carry on "doing pretty well" will rely on Foursquare pulling off one of the most public changes of direction in years. Can it say goodbye to the check-in for good?

No comments:

Post a Comment